Remembering Lani Guinier

By Gerald Torres

This post originally appeared on the Law and Political Economy Project, LPE Blog

When Professor Lani Guinier passed away earlier this month, the announcements focused on the signal events in her life: her litigation as an LDF attorney of landmark voting rights cases, her shepherding through the 1982 amendments to the Voting Rights Act, the right-wing attack that caused President Clinton to pull her nomination to head the Civil Rights Division at the Justice Department, and her appointment as the first tenured black woman to the faculty of the Harvard Law School. However, as important as these milestones were, this focus obscures the ideas that animated her life—ideas that, while they were expressed through the law and conventional politics, were rooted in a lifetime of resistance to injustice.

Lani also knew the power of stories to elaborate her ideas and build community. She was an amazing storyteller, in person and writing. And she cultivated that practice in others. Lani would recount an episode from fourth grade in which she asked the teacher why they weren’t taught that Washington, Jefferson, and other founders were slave-holders. She wondered who the three-fifths clause protected and how interests once excluded could be expressed democratically. Beginning with those ideas and her experience as a black girl, she challenged injustice where she encountered it and began to understand that inequality was the water in which we swam. Inequality was the conventional wisdom, and the culture justified it. To make a change, you had to challenge what everyone knew, and you had to risk being labeled a troublemaker. You had to stand against the powerful.

So, what were her ideas? Why did the right willfully distort her views on democracy? It may have been as simple as looking for a way to wound the President. But, more likely, it was to keep her critique of what passed as democratic processes and what would be her vigorous defense of voting rights off the agenda. She understood that voting is just one moment in the democratic process; though crucial, it did not guarantee that each vote had the same weight. She proposed that we experiment with how votes are cumulated and look to democratic practices worldwide as examples. She understood that there was no sacred way of conducting elections; they need only ensure that power is not hoarded or monopolized. Certainly, voting was about belonging, but more importantly, it was about distributing democratic governance and ensuring accountability.

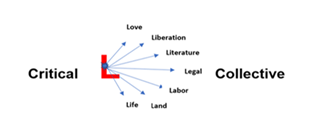

Her focus on democracy led her to challenge the institutional impediments to sharing power, including the meritocratic system that governs higher education. She understood that the problem democracy was supposed to solve could not be limited to the mechanics of voting but had to interrogate questions of power more broadly. Lani was not only about naming and calling out injustice. She called for reimagining justice and offered concrete ways to do just that. She did this in her move from testocracy to democratic merit, her focus on political race, her emphasis on racial literacy, and the paradigm of demosprudence. These concepts combined critique and affirmative vision, theory and practice, vision and realization. As a thinker, teacher, and advocate, she was both a trenchant critic and a visionary.

Of course, by looking at power, she was drawn to examine how authority was expressed. The systematic exclusion that she noted as a young girl had built-in distortions that cosmetic changes would not cure. But she also noticed something else. Aside from the elections apparatus, many political institutions were insulated from public accountability. Courts offered one venue to provide accountability, but courts themselves were not necessarily democratic guardians and, in fact, at times had to act contrary to the expressed democratic will. To justify this authority, the courts were required to preserve a deeper kind of democratic integrity.

This last idea gave rise to a concept we came to call demosprudence. Demosprudence is the study of how active civic engagement can produce durable legal changes. It is the study of how cultural transformation sometimes requires a correlative legal expression. This legal change can be accomplished through formal channels, or it can provide a new understanding of the meaning of existing legal categories. Importantly, it studies the complex social dialog that helps to animate and legitimize interpretations of existing rules or expose their infirmities. Through the mechanism of dissent, Lani showed how courts engage in this vital conversation. Importantly, they challenge the prevailing view and reinstitute dissent as an essential component of democratic lawmaking.

So, rather than understanding Professor Guinier’s work as a commentary on voting rights, you should instead appreciate her work on voting as an entry point into a far more serious and engaged inquiry into how we will make democracy work. And it will only work if power is more broadly distributed, robust avenues of accountability are maintained, and the public and the private are understood as complementary components of a democratic society. It’s not a coincidence that Lani’s work and ideas focused on two main arenas: politics and education. Both are central to democracy and to pursuing justice.